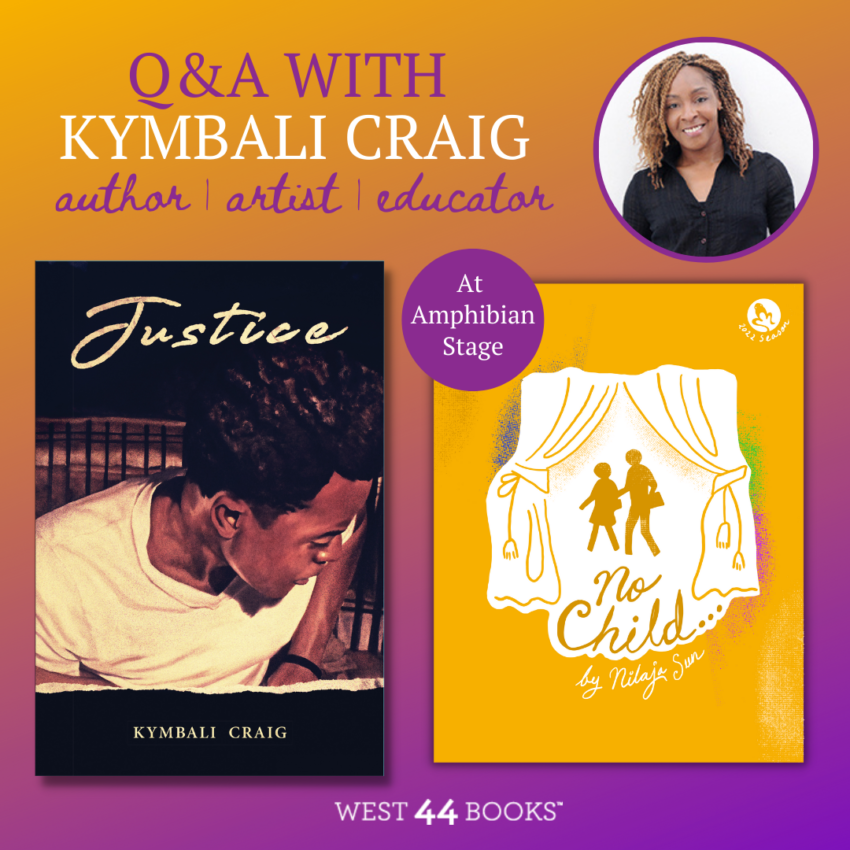

Kymbali Craig is a writer, actor, musician, spoken word performance artist, visual artist, and educator. She is a native of Chicago, Illinois, and Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and now resides in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. Kymbali was the artist-in-residence at Paul Robeson High School in Brooklyn and the creative director of Bailey’s Café, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit. Through her years of experience working with urban youth as an artist and educator, Kymbali has cultivated meaningful relationships with her students, who affectionately call her “Miss Kymbali” or “Miss K.” Justice is her first novel.

More recently, Kymbali is appearing in No Child… at Amphibian Stage in Fort Worth, Texas. Kymbali plays 16 characters in this tour-de-force exploration of the New York City public school system. An insightful, hilarious, and touching celebration of teachers and how they change lives.

West 44: Justice, the first novel you wrote, and No Child…, the one-woman play you are acting in, are both centered on school life. Why is that setting interesting to you? In what ways does your own experience inform the way you approach telling these stories?

KC: I taught as an artist-in-residence at an urban public high school in Brooklyn. I also ran a nonprofit for youth. I’ve also done several programs as a teaching artist all over the New York City area. I have a relationship with many of my former students to this day. So, I experienced these challenges firsthand. I also come from a family where education was very important. My father used to say, “Education is the key to anywhere you want to go in life.” My father knew the value of an education because he gave up the opportunity to complete his education. He dropped out of high school six weeks before his graduation, and it was a decision that followed him all of his life. Race is also important to me. I am a product of the Great Migration. Both my mother’s and my father’s families have their roots in Mississippi and moved to Chicago. I grew up in Chicago and lived in Mississippi as a teenager. The disadvantages that come from racial discrimination and disparities changed my father’s life as a young black man, and they affect the environments in which many young people of color are raised today. If a student can receive inspiration and education, it can change life outcomes.

West 44: Your novel Justice shows how teachers are human beings—capable of being inspiring and helpful, but also at times fallible. Why do you think it is important to depict teachers as human—having a dimension beyond their classroom personas?

KC: Teachers often take their lives home after work. After hours, most teachers’ lives are not their own—they call parents and grade papers, and prepare for the next day. For example, I had a student tell me that it was my job to make sure they were a success. Leading classrooms of thirty students to success requires a lot of hard work and sacrifice. It becomes easy to forget that teachers have their own personal lives outside of the classroom. They have their own goals and aspirations. The role also becomes so multifaceted due to failing public school systems. Teachers have so many additional responsibilities in financially strapped school systems and districts where standardized testing has become the focus instead of teaching and learning. In fact, the play is titled No Child… because it refers to No Child Left Behind, the law passed by Congress during the George W. Bush administration that required schools to become oriented around standardized testing but didn’t provide the funding to meet all of its demands. Teachers have become not just educators, but also take on the role of so many professionals that school districts fail to hire, like social workers and psychologists. Instead, teachers bear the burden of filling in the gap—working as counselors, mentors, and parental figures for each student. They have to stay loving and supportive even when they don’t receive the same from students. People should know what teachers are up against. It’s not a profession that receives the financial reward that it deserves. It requires so much time and personal investment outside of the classroom.

West 44: In No Child… you portray 16 different characters. How did you prepare to play such varied roles?

KC: First of all, I love character development. The assistance of my director, Craig Anthony Bannister, was a big help in helping me access the voice, the physicality, and making the characters distinct. The work of Nilaja Sun, the playwright, just jumps off the page and the characters are so well written. The director, stage manager, and I invested a lot of time in rehearsals until we got it mounted and on its feet. I’ve done several one-woman shows in the past, so I’m used to the process. I am inspired by the work of Carol Burnett, Tracy Ullman, and Anna Deavere Smith.

West 44: Which characters were the most challenging to develop?

KC: The most challenging character was Ms. Tam, the Asian-American teacher, because it was a little difficult to access the accent without being comical or stereotypical. Once the voice came, however, I went to the text and the two married immediately.

West 44: Which characters are the most fun to portray?

KC: The most fun to portray are Ms. Kennedy, the Jewish-American principal, and Coca, a Latina from the Bronx. Coca had a particular accent that many Latinx residents from the Bronx have. The more I dived into the character, the more real she became. I saw her in the subway and I saw her on the streets in New York City. Shandrica is an “around the way girl” that reminds you of a tough black teenage girl from Brooklyn or Harlem. She was fun because of her physicality and she breaks stereotypes, like the title character in Justice. She becomes the most successful of all of the students, despite how, as she put it, “They don’t expect us to do anything but drop out, get pregnant, or go to jail.”

West 44: What do you hope that audiences take away from No Child…?

KC: I would like for audience members to understand that kids’ living conditions and their environment affects their ability to become their best selves. The school system is the bridge to opportunity, a chance at a better life. If that system is filled with flaws, is outdated with books and funding, and standardized testing is the focus, the kids suffer more. I want them to take away an understanding of what urban kids are dealing with. Kids have a better chance or worse chance based on this one bridge. I want them to have more compassion for the situation they’re in and not judge them.

Buy a copy of Justice.

Buy a copy of Justice.